I’ve been honoured to cast alongside Billy on a number of occasions while we were both at Umha Aois events. His recent article for the Pallasboy Project: Art, Craft, Archaeology, and Alchemy talks about his experience in both experimental archaeology and craftsmanship.

Making bag bellows

Bag bellows might be the oldest form of bellows used. We don’t know for certain because they are made entirely of organic materials, and so none survive in the archaeological record. Because they have the advantage of being portable, lightweight, and easy to make, this type of bellows are still in use for iron forging in parts of Africa and South Asia. When you make a pair, you can be as “authentic” as you want, using only wood and leather, or you can use more readily scrounged materials like vacuum cleaner hoses and pleather. There is a remarkable video of Kenyan metalsmiths using bellows made of cement bags here.

In addition to this tutorial, check out the Bellows Forum page where there are variations of bellows designs and some interesting variations.

Traditionally bag bellows are made of pliable leather and the usual description is that a single bellow is made from one goatskin. The bellows I describe here are made with upholstery fabric. At the time I made them, leather was too much for my budget. After they were sewn I gave them a good coating of linseed oil that made them both waterproof and airtight. I find it ironic that in the Bronze Age leather would have been readily available, but hand-woven fabric would have been exorbitant. So, these are my ostentatious display of wealth bellows.

How big the bellows you make will depend on what’s comfortable for you. I’ve used very large bellows and ones so small you’d think that they’d never produce enough air to get the job done, but they did remarkably well. What is important is that the size works for you. You’ll be sitting on the ground, or close to the ground (I like a log or a short tree stump with a bit of padding). Sit down on the floor and raise your arm with your elbows bent so that they are lifted a little over waist high. Try not to move with your shoulders. You’ll be pumping your arms up and down for hours, so it’s good to find a height that works for you so that you don’t wear your arms out. Measure that height or get a good idea of how high that is. Then you’ll want to add a few more inches because you want to have the bellows rest on the ground. If you lift them too high, the sides will collapse and you won’t be able to trap the air in them. You also want to add another few inches to wrap around the handles.

Besides the leather (or whatever material you choose) the other supplies you’ll need are heavy waxed thread or sinew, leather or sail needles (depending on the type of material you’re sewing). The handles are made of two straight branches about 3-4 cm (1-1 ½ inches) in diameter, or four boards 3 by .5 cm (1 by ¼ inch) the length will depend on how wide the top of your bellows are. If you use branches, they’ll have to be split lengthwise so that they have a semi-circular cross section. My bellows are about 16 inches wide.

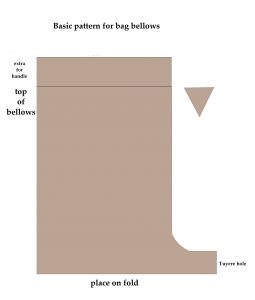

Using your own measurements, adapt the pattern below, adding about 3 cm/1 inch for the seams around the edges, and enough at the top to wrap around the handles. You’ll also need some scrap to make loops for your fingers. The loops are more important than you realise. Getting them right will mean the difference between being able to work for hours, and giving up because you keep getting blisters or losing your grip.

Another useful detail is to sew a small triangle in the front of the bellows, just below the handles. Holger Lonze taught me this trick. It makes it much easier to open the bellows wider and get more air in.

The other detail is the part at the bottom that sticks out. This is where the tuyere will fit. The size you make that will depend on the tuyere you make, and also how much air you want to push through to the fire. If it’s too narrow, you’ll be expending a lot of energy pushing air through a small space. Too large and you’ll be pumping furiously to get the volume of air through the tuyere. Mine is about 10 cm (4 inches) and tapers a little so I can fit different tuyeres to it in case I ever want to change it.

The other supply you’ll need is rawhide. Leather strips can work, but they aren’t as durable or tight as rawhide. The best source for rawhide I’ve found is the pet shop. Buy a rawhide chew bone for a dog and soak it in a bucket of water overnight. The rawhide will soften and you can untie the ends and unroll a nice sheet of rawhide. I cut it in a spiral so I have good, long pieces. While it’s wet, you can wrap it and tie it easily. Once it’s dry it shrinks to a hard, tight fit.

Cut out the leather or material and then stitch it with the outsides together so that when you turn it inside out, the raw edges will be on the inside. Don’t sew it all the way to the top. You want that extra selvedge to wrap around the handles. Make sure you fit the triangle in the front below the bottom edge of where the handles will be.

The next step was the hardest for me. It’s a bit of a pain. You need to wrap the upper selvedge of the bellows around the sticks and sew them tightly into place. If you’re using half-round branches, make sure the flat sides are on the inside so they meet and make a tight fit. Sew these in tight along the bottom of the sticks. It’s annoying if they wobble around.

Turn the bellows right side out and admire your work.

If you used branches, you might not need loops for your fingers. Try pumping them a bit and see if you can open and close them easily without them slipping out of your hands. The action is to open them while the top of the bellows is close to the ground, Lift them, close them when they are as high as you want to lift them, close the bellows and then push down. If you lose your grip, you might want to put loops on them. They are simple, just strips of the same material that your bellows are made from. Sew them so your hand will be about 1/3 to 1/4 of the way from the back. When the bellows open, the little triangle in front will allow the bellows to open in a “V” shape and allow you to trap more air. Having the loops toward the back means that you don’t have to open your hands as wide. Since I work with kids a lot, this was a consideration when I designed them. Also, I have small hands.

The loops should accommodate four fingers on one side and your thumb on the other. The handles will stretch over time, so I periodically have to stitch them again to tighten them up.

There now, try them out. If you feel any air leaks in the seams you can seal them with linseed oil. If you made your bellows from fabric, the easiest way to coat them is to hang them on a clothes line outside and slather the oil on with a paintbrush. It takes a long time to dry and smells pretty strong. It’s definitely something to be done outdoors. Keep in mind that it might take a day or two for the linseed oil to dry.

Now in order to work, you’ll need at least a short tuyere. If you’re not fussed, some steel tubing from a vacuum cleaner works fine. If you want a more Bronze Age look, you can make them from wood. I took a short branch and drilled a hole in it using a 2 cm flat bit (1 ½” spade bit in the US). The branches are about 1 cm or ½” wider than the bit. If you don’t have a bit or don’t want to use power tools, take a branch of the right thickness (about 4 cm or 3”) and split it in half. Carve out the centre and fit them back together using glue and rawhide.

Fit one end of your tuyere into the opening at the bottom of your bellows (you didn’t sew that shut, right?). Now take the wet, sloppy rawhide and wrap it tightly around the part of the bellows covering the tuyere. If your tuyere is made of split branches, keep wrapping so that it holds the halves of the branch together. Depending on the weather and humidity, it might take several hours for the rawhide to dry.

Once everything is dry, try them out. They’ll be a bit stiff at first and will need to be broken in. It takes a bit of practice to get the Open-Lift-Close-Push rhythm going, especially if you alternate hands. Once you get into it, it gets easier. Think of a cat kneading its paws.

Another tip is to get some thin willow twigs, about the size used for making baskets. Make them into hoops that will fit inside the bottom of your bellows. It will help keep them open, especially if you have a tendency to lift them too high.

Next you’ll be wanting a “Y” shaped tuyere to connect the bellows together.

World’s Oldest Needle

World’s oldest needle found in Siberian cave that stitches together human history

Bone needles are one of those things that are a useful part of any experimental kit. They are easy to make, durable, and work better for sewing leather and hide than many steel needles. If they do break, then it’s easy enough to cut off a new bit, drill a hole and sand it down to a glossy, slender tool. The best bones to use are the long bones, a humerus or femur.

Recently a particular bone needle made the news. A 7 cm needle made from a bird bone was found during an excavation in the Altai Mountains in Russia. You can read the full article here. Finding a needle in an excavation is difficult enough, but finding one intact after 50,000 years is extraordinary.

However, in this context this needle is much more than just a needle. First we must think about the technology and tools that went into making the needle. It had to be cut and shaped with stone tools, and then there’s drilling out the eye. Once we start thinking about making something as simple as a needle, suddenly an entire toolkit for making needles appears, and then there’s the other direction: how was the needle used and what was it used for? Materials such as leather, string, and textile rarely survive in the archaeological record. Could the Denisovans have been sewing hides into clothes? Making shoes? Sewing smaller skins into something larger such as blankets or tents? Did they sew these together with sinew or hair, or cord made from plant fibre? A world of missing material culture suddenly becomes imaginable.

Small things like this needle should put to rest the image of the “caveman” with ragged animal skins. These people were likely to have been sewing clothing!

Making Tuyeres

Tuyeres are the tubes that bring the air from the bellows to the furnace. They can be made of wood, ceramic, PVC pipes, copper pipes, old vacuum cleaner tubes, really whatever you can come up with that will do the job. They are usually connected to the bellows, but in some cases they can just be set close enough that the air is delivered through them to the furnace. If you have a set of two bellows, the tuyeres are in a “Y” shape, with two ends connected to the bellows that connect to a single end going to the furnace.

Archaeologically there aren’t many remains of tuyeres. There are some fragments of tubular ceramic objects that had evidence of burning on the end. However, the best example is a wooden one recovered from a Danish bog. This was the same sort of “Y” shaped one described below.

Quick and easy: Tuyere #1

One of the problems of working with kids is that they are so fascinated with flames that they sometimes don’t realise that the bellows aren’t the part that supposed to be burning. So I’ve been working on making a couple of new sets of tuyeres.

I’m under a deadline for one set, so this will be a quick and easy version. I pulled a good sized forked branch from the woodpile and cut the ends so they were fairly even. Then I got a 22 mm spade bit (in Britian it’s known as a flat bit). Then I just clamped it into a vise and drilled into the flat ends of the wood until the holes met near the centre. I removed the bark, rounded off and sanded the ends. I don’t want any bark that will work loose over time, or any sharp edges that will abrade the inside of the leather on the bellows.

I usually like one with a wider fork, but this will do in a pinch. It’s more important that the two ends are close to the same angle from the main trunk to minimise any kinks when connecting them to the bellows. The tuyere will be connected by leather tubes to the bellows and held in place by strips of rawhide. Skip down to the section on putting them all together for the details on that.

Note: Save that sawdust that you’re generating with all that drilling. It will come in handy for making moulds!

Larger and more labour intensive: Tuyere #2

The next one is another wooden tuyere for a new set of bellows I’m making. It’s larger, so the spade bit isn’t an option. Instead I cut the wood in half lengthwise and then carved out the inside with woodworking gouges. It’s all handwork, so it takes longer, but one advantage is that the diameter of the air holes isn’t limited to the size and length of the drill bit.

Once the branch was cut, I marked off where I would carve out the centre and went at it with chisels and gouges. I made the interior as smooth and as even as possible. However, I don’t smooth the surfaces that will be glued together. They already fit well and the rougher texture will help the glue bond. If you’re going for authenticity, you can use birch tar or other natural glues. If you’re pressed for time Gorilla Glue works very well. Other tuyeres I’ve seen are held together with leather and rawhide.

Another variation was made by Morgan Van Es, who hollowed out a “Y” shaped branch and then covered it tightly with leather. This is far easier than drilling holes or carving two pieces of wood and trying to fit them back together again. The tuyere definitely works!

Ceramic and other Tuyeres

If your tuyere might be placed close to the furnace (as mine accidentally was), it would be a good idea to make a ceramic extension. This is just a tube made of the same ceramic you used for making the furnace or moulds. It can be fit to the end of your wooden tuyere with leather and rawhide, as described below, and the end can go straight into the furnace. The only problem I find with ceramic tuyeres is the possibility of them breaking when being transported or if someone steps on them.

At the Terramare Village in Montale, the tuyeres they use there have a 90 degree bend. The tuyere sits on the edge of a small, shallow furnace and blows air straight down onto the crucible. It’s an Early Bronze Age design and does get hot enough to melt bronze and copper. If you don’t have much space for a furnace this would be an ideal solution. It’s also worth experimenting with different types of furnaces to get an idea of how many solutions there are to the basic question of how to melt and cast metal.

There are some beautiful ceramic tuyeres in the Musei di Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza. They are from the Terramare culture that spread through the Po Valley in northern Italy.

Click on the thumbnail to get the entire photo.

At the EAA in Glasgow, I saw a poster showing the reconstruction of a beautiful horse-headed ceramic tuyere by Katarina Botwid of Lund University. This is similar to the right-angled ones they use in Montale. You can see the tuyere in action here.

I’ve also made tuyeres using the stems of Japanese knotweed. The stems are hollow, similar to bamboo, but much softer. The plants can get over an inch in diameter and several feet tall. The stems can be easily cut with a knife, small garden shears, or secateurs, and then the membranes between sections can be broken by poking a straight stick through them.

Note: Japanese knotweed is a controlled invasive species in Britain. Any fragment of stem, leaf, or root will take root and start a new plant. They are almost impossible to get rid of once started. When I find a large stand of knotweed, I strip off any leaves and excess stems and leave them there. If I need to trim off any more once I’m home, I put it in a plastic bag and then put it in the bin.

As I said earlier, tuyeres can be made of anything that will get the job done. If you don’t need to have that “authentic” Bronze Age look, you can quickly whip something together with PVC plumbing or copper piping. It wouldn’t be glamorous, but as long as any flammable or melt-able parts are kept away from the heat of the furnace, it should get the job done.

Putting them all together

The tuyere still needs to be connected to the bellows. I usually make tubes of leather that fit the tubes coming out of the bellows and the ends of the tuyere.This allows for some flexibility and gives you a bit more distance from the furnace.

Then I tie them in place with wet rawhide. Once the rawhide is dry, they are about as secure as you can get. If the leather is soft, the tubes have a tendency to twist or collapse, so a nice solution is to get some green willow twigs and roll them into a spring. Fit them into the tubes before doing the final attachment and they’ll keep the leather tubes open and prevent them from twisting.

I also fit twisted willow hoops into the ends of the bellows to keep the leather from collapsing.

Everything is fit together and tied with damp rawhide. Once the rawhide is dry, the bellows are ready to go.

By the way, if you have a hard time finding rawhide lacing, buy a rawhide dog chew. Soak it in a bucket of water overnight and then cut it into long strips while it’s still damp. If you don’t need all of it right away, let it dry out. Then when you need it again just soak it for a few hours and it will be nice and flexible again.

The Staffordshire Hoard and Me

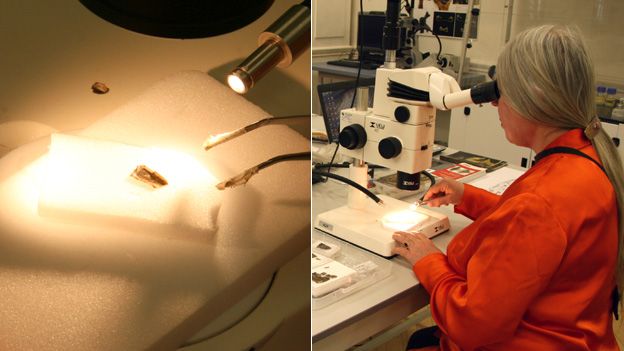

In 2015 I had the honour to be a part of the team that helped reassemble the fragments of the Staffordshire Hoard at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

Many articles have been written about the hoard, how it was found by detectorists and how the archaeological team carefully excavated the field in order to recover every fragment of gold and garnet. It was a monumental undertaking, not only for the excavation, but also for the conservation work. My job was to assemble the fragments of embossed sheet metal, some of which were a couple millimeters wide. I started by photographing and cataloguing all the fragments using a camera with the capabilities of a microscope and could stitch multiple images together. Then by rote memorisation of all the bits, and with the help of chemical analyses done by Dr Eleanor Blakelock, I started putting the fragments of the panels and friezes together. Most of my days were spent looking through a microscope while I worked, handling the tiny fragments with pairs of tweezers. I’m proud of the work I did for the Hoard and for Birmingham Museums. There are some articles and blogs that have highlighted the work I did there.

The articles and video below go into greater detail about the work I did on the Hoard and have some good photos of a few of the embossed sheet metal foil.

BBC News: Staffordshire Hoard Reveals its Secrets

Staffordshire Hoard Newsletter

Staffordshire Hoard Video Blog

The conservation of the Hoard has won a major award (November 2015). Check out the video The ICON Conservation Awards.

Casting Bronze in the Italian Bronze Age Way

In October 2015 I had the great adventure of doing some bronze casting with Il Tre de Spade (The Three of Swords) at the Archaeological Park and Open-Air Museum of the Terramare in Montale. The museum is located just south of Modena and recreates Bronze Age houses surrounded by a palisade and a marsh, appearing as it would have in the central and later phases of the Bronze Age there (1600-1250 BC). The museum hosts demonstrations and activities, along with a recreation of the original excavation.

The houses are nicely furnished, with well laid out areas for cooking, sleeping, food storage, and workshops. One house has a workbench for wood and antler working, and another area set aside for weaving and textile crafts. The other has a metalworking workbench with stone anvils, moulds, bellows, and all the needed kit stored neatly on shelves and a work bench. Unlike the recreated roundhouses that are often seen in the UK, you can get a good idea about how the ancient people lived here and where they put their all the things they used in every day life.

I had been invited to join the casting demonstrations by Claude Cavazzuti, who is also a member of EXARC. He is one of Il Tre di Spade (along with Pelle and Scacco) , who were some of the first metalworkers at the museum after it opened several years ago. They do regular demonstrations (sometimes with hundreds of visitors per day) and also run workshops that introduce people to Bronze Age casting and metalworking with a focus on the Middle and Recent Bronze Age (1700-1150 BC) of Northern Italy.

The furnaces there are small clay-lined trenches about 25 cm deep and 50 cm long, something that would be nearly invisible archaeologically and easily interpreted as a cooking hearth (and really, there’s no reason why they couldn’t be both). The furnaces heat up quickly and work efficiently. The charcoal is concentrated around the crucible with more warming beside it so that the fuel is hot before it gets raked around to cover the crucible.

My first new introduction was the bag bellows. They were larger than I have used in the past, and made of much heavier leather. They put out an enormous volume of air, and their size also allows the person pumping the bellows to sit on a low stool.

The real challenge for me was the valve and the way the bellows open at the top. The bag bellows I’d used before have straight sticks in the handles that either open parallel to each other, or are hinged at the back to open like a “V”. These bellows have two sticks on both sides, so that they open into a diamond shape making another hinge where your hands hold the bellows. It took a little bit to get used to them and to figure out where best to position my fingers. I never did get it quite tight enough and could feel a bit of air blasting on the back of my arms, but they still delivered a powerful amount of air. The tuyere was a large clay tube that curved downwards at a 90° angle, and was positioned so that it was directly above the crucible. This meant that the charcoal had to be moved frequently to keep the crucible covered. Without the layer of charcoal above, the air coming from the bellows would cool the metal in the crucible.

One nice innovation is that they put a large stone in the bottom of each bag. That prevents people who are new to bellowing from lifting them too high and causing the bags to collapse.

Casting in Stone and Sand

The crucibles are a flattened dish-shape, with some that were larger and a bit more of a bowl shape to hold more metal. They have a grooved tab on one side that is used as a handle, and have a small lip for pouring. The shallow design and lip cause the metal to pour more quickly and flow out in an arc, rather than almost straight down like the triangular bag-shaped crucibles used in Britain. It took a couple tries to get used to the trajectory of the metal in order to get all the metal in the pouring cups.

The shallow crucibles also mean that the pouring has to be done more quickly than with the deeper crucibles that I was used to. Because they are wide open, the metal cools quickly, so there is little time for dragging out charcoal and skimming. As soon as the metal was molten, we gave it a quick stir with a stick, pulled the crucible out with the wet tongs, and poured the bronze into the mould while holding the stick across the top to keep the charcoal back.

The tongs they use are beautifully crafted from wood and cord. They are kept in a bucket of water to keep them from burning when holding the heated crucible. The entire organisation of tools and materials is efficient and elegant, and there is nothing that could not have been made from materials available during the Early Bronze Age.

For this session we used the stone moulds that were on display in the house. The moulds were made of a very fine-grained local stone, the same that had been used by the Terramare circa 3500 years ago. The moulds were warmed next to the furnace and then strapped together with leather strips. We took turns bellowing and pouring.

We cast sickles, knives, and daggers using the stone moulds. Later we moved on to using sand moulds. I borrowed one of the antler spindle whorls from the woodcarving house to see if I could try casting that as an experiment. It worked sort-of. It will take a bit of work to get finished up, but I think with a couple more tries we could have got it spot-on.

I was wearing my bronze torc bracelet that day and one of the new people wanted to try casting that. We used it as a model for a sand mould and after a couple tries, we got a cast that made a perfect duplicate.

Casting a bronze sword

The museum was also performing public demonstrations that day. The main event was casting a sword using a sand mould. The sand they use is local, and perfect for casting. Commercial casting sand consists of fine sand mixed with dry bentonite clay. The sand from the Po River delta is exactly that, sand that has been reduced to almost a powder by erosion, combined with clay and silt that has been washed into the river (I encountered the same natural mixture in Albuquerque in the dry bed of the Rio Grande River Valley). The Po River sand leaves a much finer texture on the finished objects than the coarser commercial sand that I have used in the US and the UK. Looking at the quality of the sand, I was able to understand how different sands might affect the regional quality of casting, and might even have had value as a commodity.

The mould for the sword was made using the standard cope and drag method, with the pouring cup on the flat side of the sword, rather than pouring from the top. A large vent was also placed at the tip of the sword. Before casting, the mould was propped up at an angle. As the crowd gathered and settled onto benches under a marquee, Claude explained Bronze Age metalworking techniques, and then the sword was cast. The angle and the pour are calculated so that the metal cools just before it exits the vent hole at the bottom. Everyone was impressed and even more so when the perfectly cast sword was taken from the mould.

Often after the casting is done for demonstrations the bronzes are taken home and finished using drills and angle grinders, but not here. We had a relaxing time using wet sand on the hard, fine-grained anvil stones to grind off the flashing and excess metal. Some smaller stones that had a coarser texture could be held in the hand and used for working the inside curves and corners. I’d brought my small socketed hammer along and we used that to break off some of the excess metal. Between light hammering and patient grinding, the daggers were smoothed rather more quickly than I would have expected.

While we were casting, more tour and school groups came through to watch more casting demonstrations. School kids also had the opportunity to make their own copper bracelets. There was a square of tables set up with small stone anvils and hammerstones. Punches and chisels were available so they could decorate the strips of copper to make bracelets in patterns that would not have looked out of place in a Terramare village.

It was a great day, and one that was full of new experiences. It was particularly interesting to see how much variation there is in doing the same tasks and getting successful results. The different types of furnaces, moulds, bellows, and crucibles make for differences in how tasks are performed. Other small acts show variation between different metalworking groups. Tasks such as turning the crucible over to remove dross and leftover metal after casting was done into the furnace here, where in Ireland we have always done that on the ground next to the furnace. These are small things that could be seen archaeologically if excavation is done carefully, but also shows how customs and metalworking traditions develop with regional differences.

A special thanks to Il Tre di Spade, Claude, Pelle, and Scacco and the staff at the Parco archaologico e Muse all’aperto della Terramare for inviting me to participate in casting. I would also like to acknowledge Markus Binggeli & Markus Binggeli who are masters of bronze casting and replicating ancient metalworking techniques. They are mentors of Il Tre di Spade, and provide both inspiration and technical expertise for experimental archaeologists.

Useful links

If you’d like to learn more about the Early Bronze Age in the Modena area, the work of Il Tre di Spade, and the Terramare Open Air Museum in Montale you can find links below.

A film about the Terramare and Bronze Age metalworking (in English)

Il Tre di Spade also have a Facebook page.

Sedgeford Archaeology: Metallurgy and more videos!

In the summer of 2014 I had the pleasure to assist Dr Eleanor Blakelock in running week-long seminars in archaeometallurgy and experimental archaeology at the Sedgeford Historical and Archaeological Project (SHARP) in Norfolk. The current excavations are focused on two areas of an Anglo Saxon village, however their “primary objective is the investigation of the entire range of human settlement and land use in the Norfolk parish of Sedgeford”. The excavations have been going on since 1996, and the organisation provides comprehensive teaching in a wide area of archaeological subjects. You can read all about the project here.

The previous year SHARP began a new course in archaeometallurgy. Ellie wanted to expand the course, so I lent a hand with some of the hands-on and experimental work. We built furnaces, made moulds, crucibles, mixed alloys, and cast bronze. We even got some local ore to smelt iron. It was an intensive week and the hottest one I have ever experienced in England.

During the event, Ellie took some videos of us in action. The first one shows us building a pit furnace for casting bronze and a pit for heating the moulds. The video then follows us through the casting process.

One interesting phenomenon of the week was how we became separated from the rest of the SHARP community. We were given our own space that wouldn’t interfere with the the trenches or the campground, and was not archaeologically sensitive. The first two days when we were building furnaces we kept to the same schedule as everyone else. However, once the casting began we couldn’t stop for meals or keep to the schedule that everyone else had. One of our group would go down to the mess tent and bring back food for the rest of us. We were effectively isolated, although the others always knew where we were from the rising smoke. Later when we started showing up with freshly cast bronze jewellery there was a bit of envy and wonder. In the space of a couple days we had gone from being part of the community to the people who were “over there” with special knowledge, and who didn’t conform to the regular schedule or tasks that everyone else did. We kept odd hours, were continually covered in soot, but had become somewhat wizard-like in our knowledge of metalworking (not to mention regularly getting out of kitchen chores!).

On the final evening, everyone joined us for the iron smelt. The week had been intensely hot so we started stoking the bloomery furnace in the late afternoon, after the heat of the day. As the sun set and most folks had finished their supper, they came by to see the furnace in full swing with fire shooting from the top. Of course everyone wanted to take a turn at the bellows. It was a magical evening. Stories were told, and mysteries presented. The people who worked on the furnace and participated in the smelt had a new appreciation for the process of making iron. The archaeologists also had a more rounded knowledge of what a smelting site could have looked like, including the resources needed for smelting iron, and the physical space that people would have inhabited while at work. It was past 1 AM when we finally called it quits for the night and let the furnace cool.

In a way the course was an initiatory experience for the archaeologists who participated in the event. It was hard work, but they learned the secret knowledge of the smiths and have stories and their bronze castings to prove it. They also gained a well-rounded introduction to archaeometallurgy that included both theory and practice.

I have been back to help run the course and plan to be there again this summer. The course will run again this July. If you’re interested in learning more about the course or being part of the excavation please sign up on the SHARP website.

EXARC: 9th Experimental Archaeology Conference, Dublin (IE)

17-18 January 2015

I missed the first day of the conference. Instead I was at my PhD graduation ceremony. It was a wild trip. I graduated with the full regalia of cap and gown, had a quick couple glasses of wine at the archaeology department’s reception, and then we hopped on a fast flight to Dublin for the EAC9 conference at University College, Dublin. The conference was a collaborative effort brought together by EXARC, UCD, and the Irish National Heritage Park. It was a large conference with over 200 delegates, 20 papers, and 31 posters.

The Dublin University campus is huge and spread out, so we had a time trying to find the right building. I arrived just in time to deliver my paper and see the rest of the session. There were some interesting papers and posters given that explored the range of pyrotechnology in archaeology from cremation to glassworking and metalwork. In addition to the usual poster session, individual posters were given a ten minute presentation while being projected in the main hall. These included Jiří Hošek, Ryszard Kaźmierczak, Paweł Kucypera & Maciej Tomaszczyk (Nicolaus Copernicus University) with a presentation on steel carburising in a small shaft furnace, and Yuri Godino & Lorenzo Teppati Losè (University of Florence) presented a poster on their experiments on cupellating galena to produce refined silver.

I was also interested in the presentations on glassworking. There were two very different approaches to the subject with Marta Krzyżanowska & Mateusz Frankiewicz from Poland who spoke about producing Early Medieval lampwork type beads in an open hearth based on excavations in Ribe. Jonathan Thornton from Buffalo, New York spoke about replicating trade bead production based on evidence from Africa using glass frit in a clay mould .

The presentations that discussed metal began with my presentation on inverse segregation and its influence on chemical analysis of objects cast in the Bronze Age. Padraig McGoran of Umha Aois presented a poster on his experiments that included problems and solutions in casting into open one piece moulds.

After that I was off to the university’s experimental grounds to help set up furnaces and get ready for casting. The centre boasts a Mesolithic house, along with metalworking furnaces in varying states of decay. There are separate areas set aside for flint knapping, firing pottery, and active metalworking projects. The members of Umha Aois had already started building a variety of furnaces that included ones heated from below, from the side, and another with a tuyere that had a 90 degree bend that blew the air directly onto charcoal covering a flat, pan-shaped crucible. I worked at a portable ceramic furnace that was brought to the site by Fiona Coffey. It was set up inside Billy Mag Floinn’s newly constructed traveller’s tent. Despite it being wind and waterproof, the flaps ventilated it well and we kept warmer than the others who were set up under a tarp outside.

At lunch I was presented with a birthday cake. Surprisingly no one had anything bigger to cut it with than a pocket knife. The only solution was to get one of Billy’s bronze swords and carefully slice it. It was a most memorable birthday.

Bronze objects that had been created by the members of Umha Aois were on display, including swords, horns, tools, spears, and stone moulds. We spent the day casting axes, jewellery, tools, and more. There was a constant flood of visitors and regular announcements were made when one of us was ready to pour. For most of the day it was standing room only. The casting events continued all afternoon and into the evening.

Rather than head straight back to Sheffield the next day, I had arranged to see the Bishopsland Hoard and a hammer from the Garden Hill Hoard at the National Museum. I’d hoped that I could see some moulds, and to have some colleagues also examine the objects. Unfortunately emails were crossed and I just got to see the hoard and hammer. However, that was fascinating in itself, and I spent hours measuring, weighing, drawing, and photographing every detail of the artefacts.

Events like this are exhilarating and exhausting. We all learn more every time we meet, and we come away with new ideas as well as newly cast objects to finish up. This week I’ve been filing and polishing some of the bronze fibulae I cast and I still need to get to work on the replica I cast of the hammer from the Lusmagh Hoard. Meanwhile, there are more waxes and moulds to make to get ready for casting again.

Click on the link for more information about the conference EXARC: 9th Experimental Archaeology Conference, Dublin (IE)

and here is a moment by moment twitter feed from the conference

Bellows Forum

Bellows are a bit of a mystery. We know they had to have existed in the Bronze Age, but the only physical evidence we have consists of fragments of tuyeres. An Egyptian painting from the Tomb of Rekhmire, from 1450 BC shows a man using pot bellows that are operated by hands and feet. There are also Chinese documents depicting the use of box bellows. But bellows, after blowpipes, are likely to be one of the earliest forms of delivering air to the furnace. Unfortunately they are also constructed of ephemeral materials.

Until a set of bellows is uncovered preserved in a bog somewhere a lot is left to the imagination. How big or small could they be? How can the valves be altered to be more efficient? How heavy should the leather be? Should sturdiness trump suppleness? How are all the parts held together and made airtight? Bellows are one of the most essential pieces of equipment that we have for casting bronze and yet very little information is available about their origins, and we rely on information for their use and construction from the community of experimental archaeologists and reenactment groups.

Over the years I’ve seen many different shapes and sizes of bellows and always thought that a forum where bellows design and use could be discussed would be invaluable for people to share ideas and experiences.

I would like to invite others to share photos of the bellows they’ve made on this site. This could be a welcome forum for discussing the pros and cons of different designs, what worked, what didn’t. Of course any news of archaeological bellows or tuyeres discovered would add to the fun.

Bag bellows

To start, here are some photos of bellows made by Morgan van Es including a new set that were recently completed using the tutorial on this website. Morgan casts bronze at the Bronzezeithof Uelsen and Het Bronsvuur – The Bronze fire and is active on the web and Facebook discussing Bronze Age casting techniques.

Pump Bellows

I would welcome others to send in photos of their bellows, and not just bag bellows, any bellows that could be considered to fit in with what we know or can surmise from archaeology would be interesting for this forum.

Traces of Empire – Video!

Some months ago Weston Park Museum here in Sheffield approached me about making a film about how metalwork would have been done in Roman Britain. Most of what I do is related to the Bronze Age, but I jumped at the chance to do something new. We set up a time to go take a look at the brooches they would have on display. After photographing them and taking measurements, I made some waxes and then made some moulds. The process is pretty well explained in the video.

I also realised that bag bellows would probably not be the way to go, so I built the bellows that are described in the tutorial on this website.

Alan Sylvester, the filmmaker for Museums Sheffield and Lucy Creighton, (now the acting curator of archaeology) both spent long hours at Heeley City Farm helping me build the furnace and pump the bellows. After a day of filming Alan felt he needed more shots of metal being poured, and so we went back for a second day of filming. This time I had some of the pieces I cast earlier, so we could show a bit of the clean-up.

It was a great experience. Later I gave a talk at Weston Park Museum about making the film and the importance of experimental archaeology. I also brought along the bellows and some of my tools. If you go see the exhibit, there’s a shorter version of the film on a loop near the display.