Back in my undergraduate days we learned about Iron Age torcs. They were massive golden things, symbols of power and prestige. What exactly that power was, we didn’t know. They were made, used, and buried in the ground by people who had no written record. Our assumptions about power rested mainly in our own sets of values. But they are gold, valuable, and precious. Then there are other things that are just as valuable and precious, but more intangible…

A few years ago Tess Machling contacted me. She knew me as a jeweler/metalsmith turned archaeologist who had a passion for hammers and manufacturing processes. She had some photos and asked me what I thought. No details, just a question about what technique I would use to make something, or what would have caused this sort of mark. I enjoyed the puzzles. I told her how one photo was of metal that had been cracked because the smith had hammered it too much and the metal was fatigued. Could it the result of casting? No, the edges were too sharp, a casting flaw wouldn’t have a crack formed like that. In a few days I’d learn that other metalsmiths she asked told her the same things. She and Roland Williamson, a metalsmith with a background in making museum replicas, were searching for answers, and questioned everyone they could contact. Eventually I learned that we were corresponding about Iron Age gold torcs. The questions she asked us were set up like a blind test to avoid any bias. It was accepted knowledge that torcs were cast in gold and in the course of her research she was coming to the realization that the accepted knowledge was wrong.

The problems with institutions is that they lumber along and have difficulty changing. Even if they want to change, it occurs slowly. Most of the torcs were excavated and interpreted by antiquarians and archaeologists who never worked with metal and never thought to talk to someone who did. In my own research, time and again I came across ‘facts’ that had been passed along from one publication down the line that were just plain wrong. Tess and I both knew what she was up against. The entrenched ideas of institutions and people who uphold them are just as precious as gold. To have these ideas questioned seemed as great as affront as taking the One Ring from Gollum and declaring that it would be thrown into the fires of Mount Doom. But sometimes ideas do need to be cast away. Not randomly, but through careful research, examination, experimentation, and always questioning. I know that early on Tess did have doubts, but she and Roland had so much hard evidence that it was impossible to accept the status quo. Their hard work is changing the way we understand how Iron Age torcs were made. By examining tool marks they are identifying different techniques and seeing the smiths’ hands at work. They have found repairs, retrofits, and an entire catalogue of metalworking tricks of the trade.

In the course of their work, they have published articles in the The Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, The Journal of the Historical Metallurgy Society, and the Later Prehistoric Finds Group Newsletter. But research is never static, it is something that is forever evolving and growing. As we all learned through this process, entrenched knowledge is terribly difficult to dislodge, even when it’s been proven wrong. There is also a need for transparency in research, and a way for the public to learn and participate in the process, free from paywalls. By producing their new website and blog, The Big Book of Torcs, Tess Machling and Roland Williamson are presenting their work for everyone to read, and question. It’s a wonderfully informative publication with a good bit of humour that will be useful for both the layperson and the academic, not to mention aspiring metalworkers!

Tag: Iron Age

Forging Ahead!

January 2023

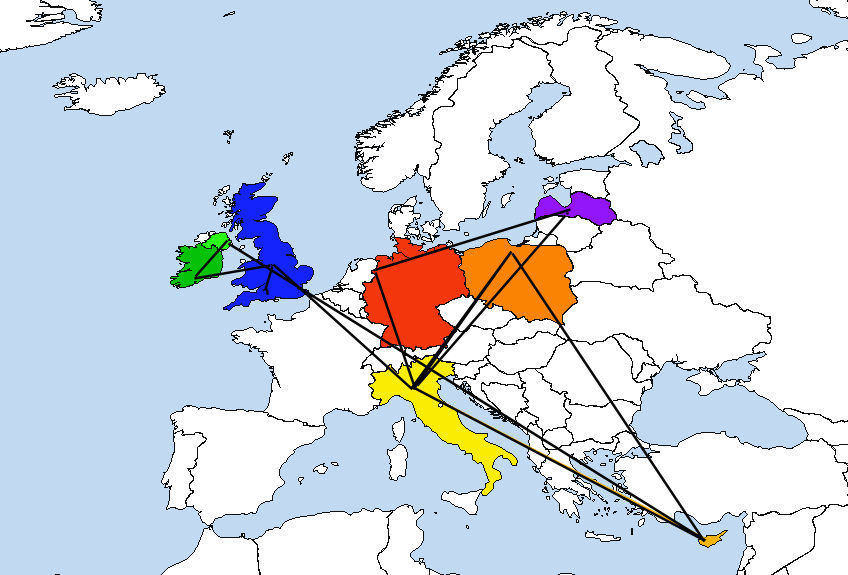

It looks like a crazy year of travel!

The year got off to a rocky start with me getting Covid while on a trip to Los Angeles. I’ve recovered and have a couple of months before I start the year’s journeys, and I am excited. It looks as if I’ll be busier than last year!

At the end of March I fly to Italy, where I’ll have a week in Modena to pick up my summer clothes and then fly to Northern Cyprus. I will spend the whole month of April there. The plan is to relax and see the country in the spring, but there’s a chance that I’ll be able to do some metalwork and give some lectures.

In May I head to Poland for the EXARC/EAC conference on experimental archaeology. Then it’s back to Italy to spend time with the family there, but at the end of the month I’ll head north to Germany for the Bronze Casting Festival, immediately followed by a trip to Latvia, where I’ve been asked to speak at a conference there.

Later in June, I’ll be in England for a couple of months where I hope to make some museum visits, help out with some workshops, and catch up with friends. In August I plan to go to Ireland and then head up to Belfast for the EAA Conference, where I’m co-chairing a session on experimental archaeology. From there, I head back to Northern Cyprus for the Vounous Symposium. I’ll spend a little more time in Italy before heading back to the US in the autumn.

Some of these workshops and travel expenses are covered by grants, but a lot of it is out of pocket for me. One of my sources of income is my Patreon Campaign. If you would like to support my work in experimental archaeology, please consider making a small monthly donation at https://www.patreon.com/archaeology Even a couple of dollars/euros/pounds a month really does help. Think of it as buying me a glass of wine after I’ve finished a day at a conference! Supporters do get benefits including postcards sent from all the places that I visit, early access to my podcast, In Small Things Considered, and special access to articles and publications that are exclusive to Patreon patrons. Special thanks go to those who support me on Patreon. You definitely are part of the excitement and fun of doing experimental archaeology!

2022 The Year in Archaeology and Conferences

2022 was an exciting year, full of archaeology, travel and travel mishaps, and exploring a world that had been closed off for two years.

In February, I finally got to work on the fellowship that was awarded to me through Historic Williamsburg and EXARC. I lived for a month in a cottage on the edge of the historic city and helped convert a jeweller’s lathe into a lapidary machine. For the final week, I was on display cutting gems in period costume, which was actually pretty comfortable. I wrote about the experience in an article for the EXARC Journal.

The year really got into gear in the spring when I landed in England and went to the Second Accidental and Experimental Archaeometallurgy Conference at the Ancient Technology Centre in Cranbourne. After two years of pandemic isolation in the US it was wonderful to be able to work with colleagues again. Before getting down to work, Fergus Milton took me over to Butser Ancient Farm to check out the new buildings. The site now has houses that range from the Mesolithic to Early Medieval and even includes a posh Roman house. Fergus is building his own dedicated metals workshop. I hope that I will get a chance to go down there and visit it when it is completed next summer.

The Archaeometallurgy conference was a great time. We constructed furnaces, laughed and joked, and shared information and stories about our respective fields of research. There were talks and presentations, a hog roast, and storytelling. Bronze was poured, iron smelted, and brass created. On Sunday the public came by to see the pyrotechnic action. They weren’t disappointed. I ended up spending more time talking to the public and explaining the event than actually working metal. That was a theme that continued through the summer.

In the end our furnaces were all destroyed and returned to the earth. By the time we left, there was little evidence that so much activity had been going on. To read more about it, here’s a link to my report in the EXARC Journal

I had a wild ride back up north with Ellie Blakelock and Vanessa Castagnino, laughing and talking the whole way. It was great to be in Sheffield again and going out into the Peak District with Gill and Ken. We checked for witches’ marks in the Tideswell Church, visited Bishop’s House, and I wandered around my old neighbourhood in Crookes.

I even got a little bit of excavating in at Castleton.

We also made a trip down to Derbyshire to visit Calke Abbey. It has one of the few remaining 19th Century faceting machines. After my experience at Williamsburg, I was interested in seeing one of these in the flesh. Calke Abbey is an experience in itself. It’s an old manor house that was donated to the National Trust, who have kept everything in situ. Everything is in a jumble, and only the library seems to have been sorted out. The director moved the machine out where I could photograph every inch of it, while Gill wrote down measurements. We did get to see more of the place, although we never got to the upstairs. As it was, there was more taxidermy than many natural history museums, and the family seemed to have a particular interest in lapidary and rock collecting. The curator in my sorely wanted to sort things out and label them, but the place is just as the last residents left it with doll houses, tiger rugs, and even a palanquin chair. It’s truly a place of sensory overload. I just wished that we could have sat ourselves down in one of the comfy library chairs and pulled out a book. A cup of tea would also have been a lovely addition.

In July I headed south and helped out with the Sedgeford Archaeological metals course, run by Ellie Blakelock. The Sedgeford Historical and Archaeological Research Project (SHARP https://www.sharp.org.uk/ ) is a long term excavation and field school. In addition to excavating an entire medieval village, they run basic and specialist archaeology courses. Despite the unprecedented heat, we had a great time building a furnace, carving moulds, and casting. The final day was an open day so the public got to see the students in action. The students had a great time and cast a lot of jewellery and small objects while learning the basics of primitive casting techniques.

The summer heat took Britain by surprise. I got a ride to the Kings Lynn Train Station. I had tickets to go from there to London and then catch the Eurostar the next morning and get back to Italy. The heat was so extreme that the tracks buckled, meaning that no trains could get in or out of Kings Lynn. After waiting a few hours I was lucky to hitch a ride with a young woman whose dad gave us a ride to Ely, where we could get the next train to London. I got a decent night’s sleep at the hotel I booked and then was up at the crack of dawn to catch the first Eurostar back to the continent.

I had a great time relaxing in Modena. I spent a lot of time at the local library taking advantage of the wifi and air conditioning. I visited friends in Siena where we visited as many museums as we could pack into a weekend. I also had some great evenings knitting with friends and making squares for the Viva Vittoria Project. In February 2023 we plan to cover the Piazza Grande with an enormous blanket, all to raise awareness about violence against women.

There was a bit too much adventure at the beginning of August when I tried to get to the Bronze Casting Festival in Uelsen in northern Germany. The plan was to take the train up near Karlsruhe, meet Kevin Frank and then we’d drive the rest of the way. Except… a couple days before we were due to leave, Kevin came down with covid. I had to figure out how to get up there by train, starting from Karlsruhe. It was the high point for holiday travel in Europe, and Germany was offering 9 euro tickets to promote public transit. The trains were packed, and always running late. I missed so many connections and kept having to cobble together a new route and schedule at every station, straining my limited German language skills. It took almost exactly 24 hours, but I got there finally. I was exhausted and then found out that other participants had cancelled out due to Covid or other issues. That left me and Matthias Fischer to get things up and running, teach, and then demonstrate to the public on Sunday. The event was only a weekend, rather than a full week, so there was little time to get my brain together. But it was good to be back, and I enjoyed the event and seeing everyone after so long.

Then I faced the trip back down south. Knowing that it would still be insane, I arranged to spend the night at Kira and Tony’s place in Köln. What should have been an early evening arrival turned into me rolling in around 11 pm. Instead of sleeping, like any sane person would, we stayed up talking and drinking wine all night. I did get a little nap in before heading back to the station. I got there on time, only to find that the first train of the morning train was delayed. The trip back had about as many delays and rescheduling as the trip up. I was so glad to be back to Italy where, despite so many complaints, the trains do tend to run on time, or at least better than they do in Germany.

At the beginning of September I flew to Budapest to speak at the EAA (European Association of Archaeologists) conference. My paper was on examining the industrial waste from primitive non-ferrous metalworking, both in ancient and modern experimental contexts. I’m hoping to continue this project and have started to look for resources and ways to support the project. Meanwhile Budapest was beautiful. I only saw a small portion of the city, and spent most of one day at the museum. I definitely have to go back again.

Then it was back to Modena briefly. I had enough time to wash my clothes and repack my bags. Then I was off to North Cyprus for the Vounous Symposium.

My goal for this year was to replicate a set of pot bellows that were excavated at Enkomi, a Bronze Age site near Famagusta. Kevin was still out with covid and Chris couldn’t afford to come, so I was on my own again. Except that Vounous is a huge supportive community. I met Ergün Arda, a ceramic artist from Turkey who took time away from his work to make the bodies for the bellows. A ride was organized so I could go to the leather supplier to get the hides I needed for the tops of the bellows. Then we had a tense night hoping that the bellows wouldn’t crack during the firing. They turned out perfectly and everyone was fascinated by them. In the following days anyone who wanted to had the chance to use them. Again, I didn’t get much in the way of casting or smelting done, but together we made an important piece of equipment that is closely related to the heritage of the site. During the symposium I finally started the Turkish language course that I’d been trying to get on for over a year. I dearly hope that I will be able to speak Turkish reasonably well by the time I return.

I always hate to leave Vounous, but at least I was heading back to Modena. It’s a good place to relax and recharge. I got to spend some time with my cousin Paolo and enjoy the cooler weather. Then in early October I headed back north to Germany to Adventon, a medieval/Viking era open air archaeological park http://mittelalterpark.de/. Kevin has been building a metals workshop there, and originally he planned for an event to celebrate the completion of the workshop. Instead, a small group of us finished putting on the roof and getting most of the walls done. Even if we didn’t get any metalworking done, it was still a great time. The weather was good for the most part, and we had a great time drinking Turkish coffee, talking, and eating meals together.

At the end of Adventon, I had to return to the US. My allotted three months in the EU were up. Unfortunately, my late afternoon flight was changed to an early morning one, meaning I had to beg a ride from Kevin, and we had to get up at 4 am to get me to the airport on time. That was not appreciated by either of us.

Back in the US, I have been finishing up a lot of projects that have languished. Knives have handles now, and I finished a sickle that was a commissioned piece. I’m at the lathe as much as possible, and I’ve also joined a foundry where I can get casting done over the winter. I have some very cool projects in mind and a lot to do in the three months until I leave for Europe again at the end of March.

Next year is already filling up. I submitted an abstract for the EAC conference in Poland in April, and the EAA in Belfast in August. There’s the Bronze casting Festival and Adventon, and of course Vounous. Speaking of which, I’ve only been in Northern Cyprus in September and very much want to see it in the spring when it is green. I’m making plans to be there in April and maybe got some metalworking done while I’m there.

2022 was an exhausting year of missed connections and difficult travel, but it was all so worth it. After the two years of pandemic lockdown, seeing so many friends and people I love, being able to work again and teach, pour metal, all of that was the greatest gift I could have asked for. Here’s to 2023 and all the adventure, but maybe with better travel connections.

September 2022

I’m back from the conference of the European Association of Archaeologists in Budapest. There were a lot of great sessions, and as always it’s impossible to see more than a fraction of what’s going on. This year the conference was a hybrid of in-person presentations and virtual. Every session had participants who joined in online. The sessions I attended went seamlessly, although it must have been tough for people on the west coast of the US who were giving their talks at 5 am Pacific Time. The poster sessions were also virtual. There were no printed posters. Instead touchscreens allowed viewers to select a session and see the posters. All of these innovations allowed for people to participate who would normally be unable to attend the conference. However, there were some people who I wish would have been able to make it, if only to have in person conversations. Still, the conference was inspiring and I came away with fresh ideas and seriously thinking about new projects.

Budapest is beautiful and the National Museum there is world class. The displays and layout are outstanding. Many of them allow the visitor to walk around the object, or at least to be able to see them from more than just one angle. The objects themselves are truly worthy of the treatment they get. I spent an entire afternoon there and would willingly go again and spend more time.

But there’s no rest this week. I arrived back on Saturday and tomorrow, the 6th I fly out to North Cyprus for the Vounous Symposium. There will be two weeks of smelting copper and melting bronze, and maybe we’ll get back into making some faience.

July 2022

The year continues, although the excessive heat has been a bit much, especially when working with hot metal!

The Accidental and Experimental Archaeometallurgy 2.1 Conference was a blast. It was great connecting with everyone again and getting some work done. Thanks to Vanessa Castignino who went all out to make the event a success. There was the usual friendly rivalry between the ferrous and non-ferrous people, with furnaces of all shapes and sizes. There will be a short review of the conference in the EXARC Newsletter, coming out soon.

After a relaxing time in Sheffield, where I actually got to do a few minutes of excavating, I headed down to Norfolk for Sedgeford’s Archaometallurgy day course. We had some great students and built a permanent bowl furnace, so we don’t have to start from scratch every year. We did try to smelt copper, but ironically the weather was too hot to continue bellowing, so we just couldn’t get the furnace hot enough without roasting the people pumping the bellows.

Right now I’m in Modena, Italy where the extreme temperatures continue. However, I am looking forward to a cool time in Uelsen, Germany where I’ll be at the Bronze Casting Festival. I plan to continue my experiments with self-draughting furnaces, and use my 3D printed pins as forms for some sand casting.

Later in August I’ll be presenting at the EAA Conference in Budapest, and then I just got word that the Vounous Symposium will be back for another year! I am so looking forward to seeing everyone in North Cyprus again. Last time we started making faience for the fun of it. Who knows what we’ll try this time, in addition to all the usual smelting and casting…

************************************************************************

2022 is finally picking up where 2020 left off. I’m back in England and this weekend I’ll be at the Historical Metallurgy Society’s Accidental and Experimental Archaeometallurgy 2.1 Conference. Next month I’ll be at Sedgeford for SHARP’s Metallurgy day course. Then in August, I’ll head up to Uelsen, Germany for the Bronze Casting Festival at the Bronzezeithof. At the end of August I’ll be speaking at the EAA Conference in Budapest. Plans are still afoot for heading down to North Cyprus in September, although I haven’t had official word about another Vounous Symposium. Fingers crossed, though. It’s an exciting event and one where we have two weeks to work rather than just a weekend.

It feels great to be on the road again, although hauling a suitcase full of bronze tools can get a bit tiring at times. Still, I wouldn’t trade this life for anything!

Welcome to 2022 and Some Resolutions

Last year, in 2021 everything was cancelled… again. The world was put on hold for another year. We all got tired of waiting for the next shoe to drop, not realizing that it was a centipede that was dropping them. It was as if the promise we hoped for in 2020 was snatched away. Some people reacted with anger, but for me it was withdrawal. I checked out for a while. When I look back on all the stuff I did last year, it looks like I was insanely busy, but to me it felt as if I had been treading water, waiting for life to come back to some form of normal and leave the US behind. Still, hope springs eternal. My fellowship at Colonial Williamsburg that’s been delayed three times is rescheduled to happen next April and with luck I’ll be back in Europe this summer.

I did get a furnace built last year. It’s self-draughting, so I didn’t even need a set of bellows. That was convenient and a real labour saver, but it brought home how much bronze casting is a communal event for me. I missed the camaraderie, the laughing, storytelling, and the intensity of working as a close-knit team. I never bought into the idea of the lone, itinerant Bronze Age metalsmith, unbound from the structure of society. As a metalsmith, I am pretty itinerant, but I am rarely alone, and there is always some sort of social structure. In the modern world it is much easier to do this sort of work alone, but that is essentially an illusion. I head over to the hardware store and buy bags of charcoal and order bags of clay to be delivered here, but in the Broze Age there would have been a lot more interaction to get the necessary supplies. If the people who dug the clay and burned the charcoal weren’t a part of my village or settlement, I would have had to negotiate how to get the supplies to where I was working. Likewise for the metal or ore. The Bronze Age was a world without a lot of easy transportation. Something we take for granted now.

These days it’s unfashionable to do New Year’s resolutions. People point out that there really isn’t anything special about the transition from December 31st to January 1st, it’s just an arbitrary date. It is an arbitrary date, but it’s also a long-standing tradition and there is a certain amount of power in traditions. 2021 was certainly a depressing year. Then New Year’s came and went. Compared to New Year’s Eve in Italy and England, there’s not much going on here even in a non-Covid year. It was a low point for me, and it came to the point where the only way was back up again. So, I did make resolutions. Small ones that will get bigger as I get back into the swing of things. It felt right. I feel as if I am getting back into the game and even if I don’t have a lot of energy, I’m acting as if I do. In the coming weeks I plan to put up a page of bronze casting moulds, similar to the page I made for textile tools. I’ll also write a full report on my self-draughting furnace, that amazingly seems to be holding up in the sub-zero weather here, and I’ll polish up and publish some old articles of mine. So, I’m back and hoping to make up for lost time.

Iron Age Shoes

Sometimes you just need a new pair of shoes. I’d been wanting to make some of the replica shoes I’d seen online. there are a few good sites where you can find patterns and step by step tutorials.

Kelticos has a number of different patterns that you can download.

I followed the instructions on this site. It goes step by step and practically no-fail. I however am a bit more cautious and rather start with the leather I made a pattern out of brown paper.

Once I was confident that I had a good fit with the paper pattern, I bought the leather that I needed. One thing that few sites describe is the type and weight of leather needed. I bought some cow leather that was supple, but not stretchy from Cox Leather in Albuquerque. The place is an amazing resource for hides, rawhide, leather, skins, and really anything leather related. They also ship!

Leather thickness in the US is measured by the ounce, and in mm in Europe. The leather I bought was about 8 oz / 3.2 mm / 1/8 inch thick.

Once I traced the pattern on the leather, I cut the shoes out using good sharp scissors and punched the holes for lacing with an awl. It’s important to use an awl or punch rather than cutting the hole with a scissors since a round hole pushed through the leather is less likely to tear than a hole that is cut.

I stitched up the backs with sinew. I followed the directions and stitched the sides of the heel to the heel tab straight up. It ended up a little loose. When I get the time I’ll restitch them so they come in a little tighter on the top. Another modification will be to put more of a sole on them. Some options are to cut an insole out of rawhide and sew it between the inside of the sole with another, softer leather insole on top. I might line it with some sheep skin, too.

First posted on 16th November 2016

Since I first posted this I have worn the shoes often and have come in useful while working at the Bronzezeithof in Germany. They are holding up well after a year, although I don’t wear them every day.

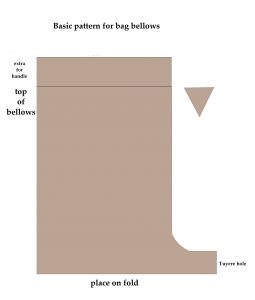

Making bag bellows

Bag bellows might be the oldest form of bellows used. We don’t know for certain because they are made entirely of organic materials, and so none survive in the archaeological record. Because they have the advantage of being portable, lightweight, and easy to make, this type of bellows are still in use for iron forging in parts of Africa and South Asia. When you make a pair, you can be as “authentic” as you want, using only wood and leather, or you can use more readily scrounged materials like vacuum cleaner hoses and pleather. There is a remarkable video of Kenyan metalsmiths using bellows made of cement bags here.

In addition to this tutorial, check out the Bellows Forum page where there are variations of bellows designs and some interesting variations.

Traditionally bag bellows are made of pliable leather and the usual description is that a single bellow is made from one goatskin. The bellows I describe here are made with upholstery fabric. At the time I made them, leather was too much for my budget. After they were sewn I gave them a good coating of linseed oil that made them both waterproof and airtight. I find it ironic that in the Bronze Age leather would have been readily available, but hand-woven fabric would have been exorbitant. So, these are my ostentatious display of wealth bellows.

How big the bellows you make will depend on what’s comfortable for you. I’ve used very large bellows and ones so small you’d think that they’d never produce enough air to get the job done, but they did remarkably well. What is important is that the size works for you. You’ll be sitting on the ground, or close to the ground (I like a log or a short tree stump with a bit of padding). Sit down on the floor and raise your arm with your elbows bent so that they are lifted a little over waist high. Try not to move with your shoulders. You’ll be pumping your arms up and down for hours, so it’s good to find a height that works for you so that you don’t wear your arms out. Measure that height or get a good idea of how high that is. Then you’ll want to add a few more inches because you want to have the bellows rest on the ground. If you lift them too high, the sides will collapse and you won’t be able to trap the air in them. You also want to add another few inches to wrap around the handles.

Besides the leather (or whatever material you choose) the other supplies you’ll need are heavy waxed thread or sinew, leather or sail needles (depending on the type of material you’re sewing). The handles are made of two straight branches about 3-4 cm (1-1 ½ inches) in diameter, or four boards 3 by .5 cm (1 by ¼ inch) the length will depend on how wide the top of your bellows are. If you use branches, they’ll have to be split lengthwise so that they have a semi-circular cross section. My bellows are about 16 inches wide.

Using your own measurements, adapt the pattern below, adding about 3 cm/1 inch for the seams around the edges, and enough at the top to wrap around the handles. You’ll also need some scrap to make loops for your fingers. The loops are more important than you realise. Getting them right will mean the difference between being able to work for hours, and giving up because you keep getting blisters or losing your grip.

Another useful detail is to sew a small triangle in the front of the bellows, just below the handles. Holger Lonze taught me this trick. It makes it much easier to open the bellows wider and get more air in.

The other detail is the part at the bottom that sticks out. This is where the tuyere will fit. The size you make that will depend on the tuyere you make, and also how much air you want to push through to the fire. If it’s too narrow, you’ll be expending a lot of energy pushing air through a small space. Too large and you’ll be pumping furiously to get the volume of air through the tuyere. Mine is about 10 cm (4 inches) and tapers a little so I can fit different tuyeres to it in case I ever want to change it.

The other supply you’ll need is rawhide. Leather strips can work, but they aren’t as durable or tight as rawhide. The best source for rawhide I’ve found is the pet shop. Buy a rawhide chew bone for a dog and soak it in a bucket of water overnight. The rawhide will soften and you can untie the ends and unroll a nice sheet of rawhide. I cut it in a spiral so I have good, long pieces. While it’s wet, you can wrap it and tie it easily. Once it’s dry it shrinks to a hard, tight fit.

Cut out the leather or material and then stitch it with the outsides together so that when you turn it inside out, the raw edges will be on the inside. Don’t sew it all the way to the top. You want that extra selvedge to wrap around the handles. Make sure you fit the triangle in the front below the bottom edge of where the handles will be.

The next step was the hardest for me. It’s a bit of a pain. You need to wrap the upper selvedge of the bellows around the sticks and sew them tightly into place. If you’re using half-round branches, make sure the flat sides are on the inside so they meet and make a tight fit. Sew these in tight along the bottom of the sticks. It’s annoying if they wobble around.

Turn the bellows right side out and admire your work.

If you used branches, you might not need loops for your fingers. Try pumping them a bit and see if you can open and close them easily without them slipping out of your hands. The action is to open them while the top of the bellows is close to the ground, Lift them, close them when they are as high as you want to lift them, close the bellows and then push down. If you lose your grip, you might want to put loops on them. They are simple, just strips of the same material that your bellows are made from. Sew them so your hand will be about 1/3 to 1/4 of the way from the back. When the bellows open, the little triangle in front will allow the bellows to open in a “V” shape and allow you to trap more air. Having the loops toward the back means that you don’t have to open your hands as wide. Since I work with kids a lot, this was a consideration when I designed them. Also, I have small hands.

The loops should accommodate four fingers on one side and your thumb on the other. The handles will stretch over time, so I periodically have to stitch them again to tighten them up.

There now, try them out. If you feel any air leaks in the seams you can seal them with linseed oil. If you made your bellows from fabric, the easiest way to coat them is to hang them on a clothes line outside and slather the oil on with a paintbrush. It takes a long time to dry and smells pretty strong. It’s definitely something to be done outdoors. Keep in mind that it might take a day or two for the linseed oil to dry.

Now in order to work, you’ll need at least a short tuyere. If you’re not fussed, some steel tubing from a vacuum cleaner works fine. If you want a more Bronze Age look, you can make them from wood. I took a short branch and drilled a hole in it using a 2 cm flat bit (1 ½” spade bit in the US). The branches are about 1 cm or ½” wider than the bit. If you don’t have a bit or don’t want to use power tools, take a branch of the right thickness (about 4 cm or 3”) and split it in half. Carve out the centre and fit them back together using glue and rawhide.

Fit one end of your tuyere into the opening at the bottom of your bellows (you didn’t sew that shut, right?). Now take the wet, sloppy rawhide and wrap it tightly around the part of the bellows covering the tuyere. If your tuyere is made of split branches, keep wrapping so that it holds the halves of the branch together. Depending on the weather and humidity, it might take several hours for the rawhide to dry.

Once everything is dry, try them out. They’ll be a bit stiff at first and will need to be broken in. It takes a bit of practice to get the Open-Lift-Close-Push rhythm going, especially if you alternate hands. Once you get into it, it gets easier. Think of a cat kneading its paws.

Another tip is to get some thin willow twigs, about the size used for making baskets. Make them into hoops that will fit inside the bottom of your bellows. It will help keep them open, especially if you have a tendency to lift them too high.

Next you’ll be wanting a “Y” shaped tuyere to connect the bellows together.